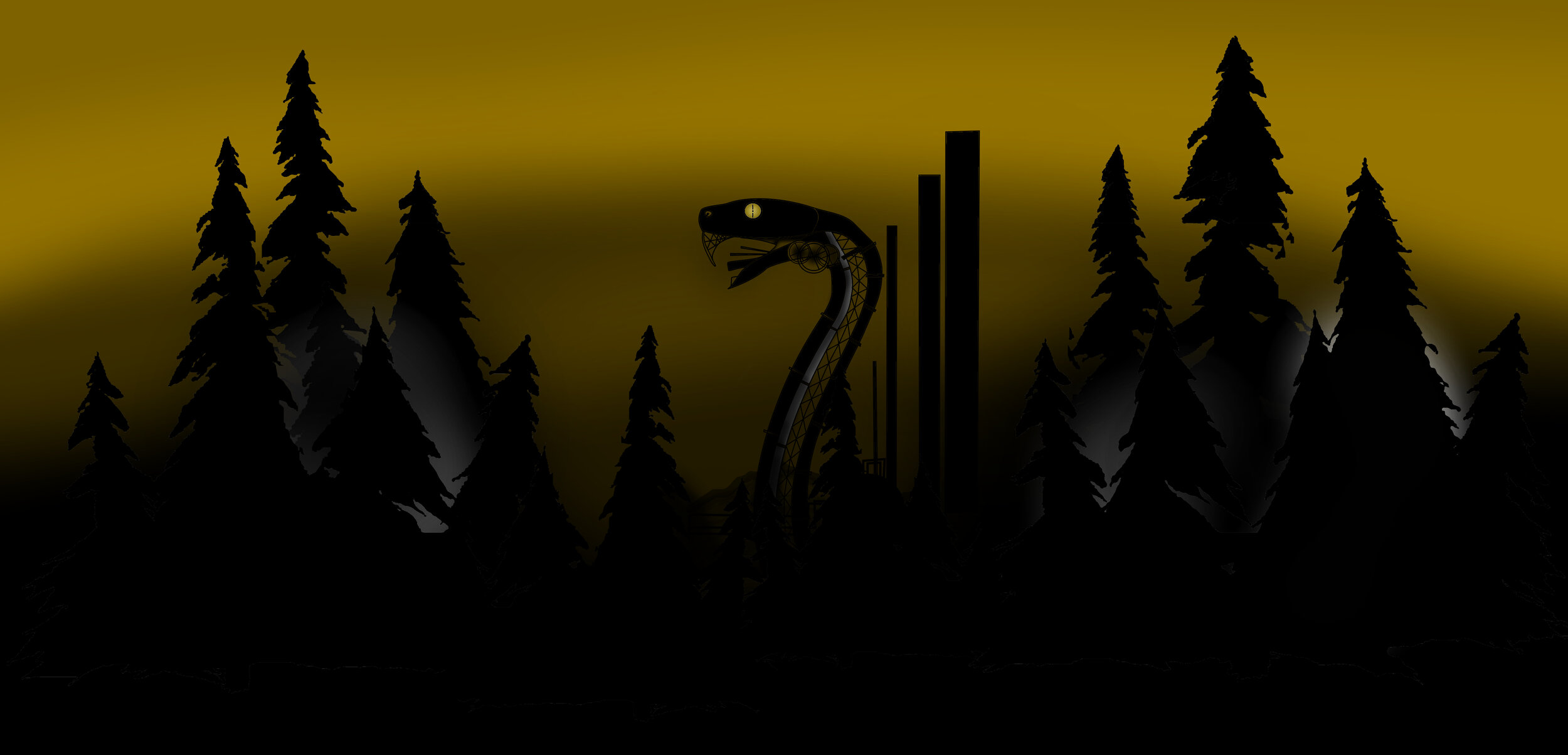

tar sands and the trans mountain pipeline

What is the trans mountain pipeline?

The Trans Mountain pipeline (TMX) is a 1000 mile long oil pipeline from Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, to Burnaby Inlet in Vancouver, British Columbia. A spur of the TMX crosses the northern colonial border at Sumas, WA, and continues to Anacortes, WA. The remainder of the product is loaded onto barges and tankers and sailed to destinations along the West Coast of the United States and to Asia. The pipeline was built in 1953 with a capacity to transport 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) of diluted bitumen. In 2013, TMX’s former owner Kinder Morgan began work to install a second, larger pipeline alongside the first one, effectively tripling its capacity to 890,000 bpd. In 2017, Kinder Morgan sold its stake in TMX and this expansion project (TMEP) to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Canadian government. Construction is ongoing at this moment.

what is diluted bitumen?

Diluted bitumen is a form of heavy crude oil that is produced from the tar sands, the ground beneath the formerly pristine boreal rainforest, the last old growth forest in North America, where unceded indigenous peoples have lived since time immemorial, and species at risk of extinction live.

Bitumen itself is a sticky oily substance suspended in sand under existing land, or “overburden”. Extracting it is energy intensive; it is literally cooked away from the sand using clean water from the Athabasca river delta and glacial meltwater, which is then “recycled” i.e., by dumping the toxic effluent into the surrounding landscape, poisoning the people, fish, animals, land, and water. The result is diluted using a cocktail of some of the most toxic chemicals on Earth including benzene and toluene and sent along the pipeline for export. This highly corrosive heavy oil, diluted bitumen (for short, “dilbit”) also contains some amount of sand, thereby increasing the risk of an oil spill in the existing line, as the TMX was not designed to carry dilbit.

If spilled in water, dilbit’s characteristics of sinking rapidly while releasing toxic solvents into the water and air make it impossible to clean up.

Before tar sands fossil fuels can be turned into gasoline and other petrochemical products, the bitumen must first be separated from the land, then diluted to “dilbit” for transportation before being “upgraded” to “syncrude”, where it is finally similar to standard crude oil. From there it is refined into products. If this process seems long and complex, that’s because it is, and consequently resource intensive.

what are the tar sands?

The tar sands are deposits of bitumen mixed with sand that are found in a large portion of Northern Alberta, Canada about the size of Florida. The once pristine boreal forest and the last temperate rainforests in North America are either mined using open pits that resemble enormous strip mines, or are extracted through injection wells. A vast grid of cleared corridors known as “seismic lines” are cut across much of this area.

Where bitumen is close to the surface, the land is completely removed. Individual open pit mines may be as large as the size of Manhattan. As a result, the surface of the land is permanently destroyed and poisoned. As of a few years ago, just 0.015% of the land had been “reclaimed.”

In areas where the “overburden” (forest and layers above the bitumen) are too thick, injection (also called “insitu”) wells are used. These use a variety of processes that resemble fracking, all of which involve super heating water and chemicals to dissolve the tar from the sand in an irreversible process that literally cooks the earth below. These wells may appear to be less destructive to the land and water than the open pits, but the damage is just as insidious, depleting groundwater, and spilling saltwater onto the surface. The seismic line grids cleared around insitu wells have resulted in the forest being separated into blocks, causing especially large disruption to some of the larger animals that require uninterrupted tracts of land to hide and feed. No meaningful attempt is made to remove equipment or restore the ecosystem, and as such, well pads that dot the landscape can be seen from space as dots on a checkerboard of seismic lines.

The tar sands is the largest industrial project on the planet, and its impacts are significant in terms of global warming. Due to the multiple stages of refinement, oil produced from dilbit contributes 58% more greenhouse gasses than conventional oil. NASA scientist James Hansen has said that developing the tar sands would be game over for the climate. Allowing any of the major dilbit pipeline projects to proceed, such as Keystone XL, Enbridge Line 3, or TMEP, would cement this projection into reality.

The toll on indigenous people harkens back to the days of pioneer “manifest destiny”. Indigenous people and especially indigenous women are targeted and are reported missing, abused, assaulted, and killed, at a disproportionate rate. Indigenous land which used to support communities autonomously, is now taken at will to facilitate new tar sands development, causing settlements to find themselves surrounded by open pits. Cultures which could, only a generation ago, hunt and drink fresh water now find themselves importing processed food from abroad. The only fresh water now comes from a plastic bottle.

And the only economy available to them now, is to work for the oil companies. Companies that will have moved on in fifty years, leaving devastation for the indigenous people to deal with.

Why should I care?

Beyond the impacts of bitumen extraction, the irreparable dangers of pipeline spills along the existing and expanded TMX route, and even the long-term climate ramifications of exporting the contents, there are immediate reasons why residents in the Salish Sea area should be concerned about the pipeline.

As mentioned elsewhere, 890,000 barrels per day of bitumen will cause a 700% increase in tanker traffic through the waters of Vancouver, around the San Juan islands of WA, and the straight of San Juan de Fuca north of the Olympic Peninsula. This route would lead tankers through narrow hazardous areas such as Haro Straight off of Stuart Island, and especially of concern is Burrard Inlet near Vancouver.

Spills in these locations would not stay local, but would affect a wide area, causing the sea to become toxic into the Seattle area, destroying local ocean based economies, and dealing a grievous blow to the already tenuous Southern Resident Orca population.

A tanker spill would be an unmitigable disaster. We would never be the same.